[Gerry Berreman’s letter on the VDC is in a separate post under his name. It is a tagging error I don’t know how to fix]

Low woman on the totem pole

During my limited free time at Berkeley, I hung around a lot in the anthropology students’ break room on the second floor of Kroeber Hall, which housed the anthropology and art departments and the anthro museum. The Gifford Room was usually the scene of loud and passionate political arguments and in the center of those was someone close to Frank Bardacke. I was very impressed by these conversations, not the least because this man and his friends were among the leading lights scholastically in the department. They were graduate students and teaching assistants. Some were FSM bustees and so I was very open to what they might have to say. I was drawn into antiwar activities mainly because of these conversations and the ones I had with my sometime boyfriend in the Environmental Design department. Although I did some typing and envelope stuffing and phoning for the newly formed Vietnam Day Committee and attended every teach-in and large march, I was definitely among the followers, as opposed to the leaders, as I was in relation to all the political movements the entire time I was in Berkeley. This is not to say that I was a “blind” follower–I was as skeptical and questioning as anyone, perhaps more so because of my hardship background. It is merely to say that I was not a leader.

Just how true that is can be illustrated with the following story that occurred during the filming of the documentary “Berkeley in the Sixties.” It so happens that I was the first talking head interviewed and, for reasons I can’t explain, had a lot of face time in the trailer that was produced halfway through production to show at events held to raise the money to finish the film. At the point when that trailer was shown to a large audience in San Francisco, I was also the only woman, a situation I had already pointed out to producer/director Mark Kitchell and about which I was already a trifle uneasy. He told me that he had approached Bettina Aptheker, and been turned down. It was a problem because, in fact, there were only a handful of visible female leaders in any of the Berkeley political movements, until the women’s movement, which I missed because I had already fled to the country.

When a break in the showing came, all the women stampeded to the rest room at once and formed a line. I knew the break was coming and had seen the trailer, so I anticipated the line and was already in a stall when the crowd, talking loudly and rapidly, got there. A major voice was complaining, “Why aren’t there any women in this? Who is this nobody they put up there as the only woman? Where is Bettina?” Many voices agreed and no one knew who was the nobody. I finished up, stepped out of the stall and was met by instant silence, though not so instant that I could not spot the loudest complainer, a woman I later learned was the wife of a prominent San Francisco Chronicle political columnist, followed closely by lefties, whose name I can’t remember. (Bob Mandel? Bill Mandel?)

There was a bit of a breathless pause in the room as everyone watched to see what I would do. I smiled at all and sundry, faced the columnist’s wife, so short that even I could look down at her and said, “Well, there do exist people in the world who don’t count me as a COMPLETE nobody, but I certainly agree with your point and have suggested to Mark that he ask Jackie Goldberg.” The tension dissolved and the leader of the pack disappeared wordlessly into a stall as I calmly washed my hands and a few of the women made it a point to smile at me.

I was included in the film with all the leaders, Mark joked, as “the token follower,” to represent all those student activists who were not leaders and were only deflected from their lives as serious students by the seriousness of the situation. I pointed out to him, long before the SF showing, that the only follower among the interviewees should not also be the only woman. Though I will claim to have been a bit of a leader in the counter-cultural community I later moved to (see my other blog Sojourn in the Land of Shum on this website), at Berkeley I was so intimidated by the prestige of the university, the anthro department and pretty much everything and so awestruck that I had managed to get there, that I only offered my opinion on anything in the relative safety of the break room, where I had some friends who might defend me in a pinch, unless it was a pinch of their own creation. Only once did I speak up in public, story below as a note in the Life article posted here.

Vietnam Day Committee

The Vietnam Day Committee was the first political cause in which I was involved after my arrest in the Free Speech Movement. I had been greatly relieved when that controversy seemed to be over and I was eager to focus my entire attention on becoming, against all odds at that time and maybe even now, that strange being, a female anthropologist.

One day, Mario Savio was giving some sort of wrap-up speech on the Sproul Hall steps, maybe because our trial had finished up that summer. I was at the edge of the crowd and had actually begun to walk away to get back to my job at the Lowie Museum when I heard him say, “Now, all of you people who are out there at the edge of the crowd walking away, don’t think its all over. We have a war to stop.” I knew dimly that there was a war, and I had known that only because I had accidentally picked up an abandoned Life Magazine while a student in Georgia and seen the famous picture of the Marine holding a baby with a hut burning behind him. I remember thinking, where the hell is Vietnam? But, I had not really been updated on that subject in 2 or 3 years, since I had no TV and read newspapers only sporadically. It was not at the top of my consciousness. Hearing Mario, I stopped in my tracks and thought, “War, what war?”

Sometime after that, I saw a picture of a Vietnamese Buddhist priest on fire, having set the fire himself to protest, I assume now, the increasing involvement of the American military or the actions of the South Vietnamese government. I assure you I knew the specifics then, I’ve just forgotten some now as they have been superceded by nearly 50 years of activism. I was stunned that anyone could or would set themselves on fire and resolved to learn more about it.

Life magazine and the Vietnam Day Committee

Though I have much negative to say about the article presented below and will say it, I have come to appreciate that it well presents the “color” (as journalists say) in the VDC story, along with allegations I have no reason to dispute. Since I was too busy to write anything but my anthro papers and my memories are so loaded with the pain of my experiences, I now find it valuable to have the report of a spy presumably following the journalistic ethic of objectivity. Of course, at this point in the twenty-first century, I have to adjust my sexism detector in order to filter out the unremitting presentation of women activists as “girls”, trophies or servants, but that is an adjustment with which I am extremely familiar.

I appreciated the article even more after my own brief five-year career as a journalist, understanding now just what he did. I hasten to say, however, that I myself, have never and would never infiltrate anything in order to write about it. I’m even a little antsy about Gloria Steinem infiltrating the Playboy Club to write about it. I’m too much an anthropologist. I would have said up front who I was and what I was doing, and then worked to convince those around me that I would write a fair article. As a “member” (insofar as anybody can be said to have been a member of any Berkeley movement) of the VDC, I’m guessing his article would have been just as good, maybe better, without the spy part.

A word on Communists, since they figure prominently in this article. In my lifetime of activism, I have met, to my knowledge, four people who actually were or had been members of the Communist party. All four are women and all four repudiated the party soon after the 1960s. Only the first one had any influence on me. Before I was arrested in the FSM and when I was a student at Oakland City College and one of the founders of SLATE there, this woman said to me, in the middle of a discussion about the civil rights movement in the South, “its not just the South, its not just states, its not just the U.S. government. Its the capitalistic system. The whole thing is rotten to the core and it will implode eventually,” or something similar.

This was a major new idea to me. I still had some faith in the federal government, which was the only force for justice in the South I had just left. I had known before that statement that she was a Communist and had been keenly observing her to see if anything she did matched the picture presented in the various forms of anti-Communist propaganda I had been exposed to. That was the very first thing that fit the picture, but I have to say, it was a perfectly valid idea for a social scientist to think about and I did and I now think the whole capitalistic system is rotten to the core, as well as the economic and political system of Communist countries and that both will implode eventually for ecological reasons unless something changes in both systems. It is industrialization that is the problem in both cases, but I digress. . . .

Later, at Berkeley, I read Karl Marx, described by one of my professors as the greatest social scientist of the 19th century and found that, having been raised a Christian, I agreed with him on just about everything, including his characterization of religion as the “opiate of the masses.” It all certainly squared with my experiences at the Bible college in Georgia. Today, I would add to his work much that has emerged from human ecology and the women’s movement, but I still agree with my professor about his status as a pre-eminent social scientist.

And, please note, those people known as Communists departed greatly from Marx’s work and Marx has been irrationally and hysterically badmouthed in many ways for a long time. His analysis of capitalism is being proven as I type. Also, please note, I am a devoted follower of Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr. but was never a “follower” of Marx, in any but the academic sense.

In one of life’s strange little twists, I became reacquainted with my former Communist friend at the FSM 30th reunion in Berkeley, where she was passing out feminist flyers. I would not have recognized her if her name had not been printed on the flyer. When she handed it to me and I saw her name, I immediately looked up and asked a question and recognized her voice. I could hardly wait to corner her later and introduce myself and ask her if she still thought the capitalistic system was rotten to the core and would implode.

She was a trifle chagrined that I remembered that phase of her life and hastened to explain that she had been only quoting from the sayings of her then-boyfriend and had gone way past the point in her life where she allowed herself to be so influenced by the men in it. But, I never could get her to answer my question, though she did say she had renounced the Communist Party. We reminisced some about our days at Oakland City College and caught up on the intervening 30 years, both of us delighted that the other was still an activist. I gave her a copy of my book and we parted both somewhat bemused, I think, but certainly cheerful. I don’t know what she might have been thinking about me, but I was thinking about her, “this nice maternal harmless looking lady is someone I was supposed to be afraid of? Ridiculous!”

My basic stance all through the 60s and to this day is non-violence. I wavered briefly during my VDC days, but I snapped right back and dropped out of everything when it seemed to me that I had gotten closer to violence than I wanted to. And, the only Communist I met through my political activity in Berkeley was Bettina Aptheker, whose former affiliation is no secret, and I actually met her through mutual friends, not any political organization. The point is, I think the author below was a little heavy on the Communist angle. There were no discussions about Communism anywhere around me in Berkeley, except for the loyalty oath I had to sign to work at the museum, maybe one of the last times anyone was required to sign one. It included a two-page list of specific organizations I had to check “No” next to, indicating that I was not and had never been a member. The list consisted almost entirely of organizations I had never heard of, some of them seeming pretty absurd, such as the Romanian Folk Dance Society.

The article below has been scanned and converted to text for posting, but everything that appeared in the article has been presented, including photos and pull-quotes. There were many articles written about us at the time, though I don’t know if there were any others written by infiltrators. I happened to hang on to this one because my picture appears, sort of, and I am basically such a hick that I was quite excited that Life magazine contained a partial picture of lil ole me.

From Life Magazine, date unknown but between 1965 and 1967, pp. 107-125:

‘Go to V.D.C. house, say I sent you’

In September, LIFE Reporter Sam Angeloff, using his middle name, Tony, joined up incognito with the antiwar Vietnam Day Committee at the University of California (Berkeley). To learn how marches like those shown here happen, he spent four weeks helping organize them.

by SAM ANGELOFF

In the wide area between the administration building (Sproul Hall and the Student Union a dozen card tables stood around a small fountain. Hundreds of people were chatting, buying literature, debating—a hash of civil rights groups,political parties, teachers’ unions, religious clubs and anti-war organizations.

All this, a student at one table explained, was the fruit of the Free Speech Movement, which last year rent this great university, with its enrollment of 27,000. In a bitter battle the F.S.M. students won the “right” to engage in on-campus political activity, and they are now allowed to use university property—including classrooms—for fund raising, recruitment, debate—practically anything political. Around an oversized metal table put there by the Vietnam Day Committee (V.D.C.) about 50 people stood in a three-quarter circle while a man debated several critics. He was afleshy dark-jowled fellow who had black, uncombed hair and thick eyeglasses, and he poured out a steady stream of words:

“Now, you say the Vietcong are Communists, and therefore they’re bad. Well, hell, before anybody called them the Vietcong these same men were called the Viet Minh, and they were anti-French, and as soon as the French pulled out, the Americans got into the act and—shut up, let me finish—the people didn’t have a chance, so they had to go to the Communists for help. Did you read, did you see it, where General Ky said his only hero is Hitler? Now when you [pointing to a different critic] say the people are behind a government like that, well, that’s a lot of bull. Now, who wants to buy a book—Bob Scheer’spamphlet, 75¢. . . .”

When the debater shuffled off to get something to eat I asked his replacement if the committee needed volunteers. He was sifting through leaflets and bumper stickers, and he mumbled, without looking at me, “Oh, sure . . . yeah . . .we need . . . volunteers.” Suddenly his head snapped up and he said quickly: “Look, take this address and go down to the V.D.C. house and tell them I sentyou and you want to work. Okay?”

V.D.C. headquarters was a 10-minute walk from the campus in a three-story rooming house with dirty pink paint and sagging front steps. A broken front window was covered by a cardboard sign: “Vietnam Day Committee.” The V.D.C. had rented the ground floor. I pushed my way past the front door and into a dimly lit hallway. A door to the right led into a living room cluttered with couches,wooden chairs and a bed. The couches were stained and burned by cigarets, and the gray rug was gritty and worn. Two walls were used as bulletin boards, and on a third hung a large and gloomy collage—dozens of sneering images of President Johnson, laughing and holding bombs and rockets. A single bare bulb hung from a ceiling fixture.

Opposite the entrance was a dirty white door which led into the work room, where three typewriters rested on a long T-shaped table made of one-inch plywood and old cement blocks.

“Can you type?” a girl asked me.

“A little.”

“Good. We got these names and addresses from a sign-up sheet we have on campus. You can type them onto these address stickers. Type hard, four carbons. We put them on leaflets and fund appeals and things we mail out.” The girl was thin and had dark hair, faded-suntan skin and an Eastern accent. Her name was Nanya. In time she told me she was eligible to teach in New York and that she had worked in a Colorado ski resort. She was getting about $100 a month from the V. D. C. as “office manager.” When I asked why she had quit her other jobs, she shrugged and said she didn’t really know.

In an hour and a half I finished up the address stickers, and Nanya said my typing job was so good I should be rewarded. She produced a button that read BRING PEACE TO VIETNAM—SUPPORT THE NATIONAL LIBERATION FRONT. She said it was about the most prestigious button around; she also warned that it wasn’t an official V. D. C. slogan. I dropped a quarter in a “donation” jar, hauled a beer out of the office refrigerator, drank it and left.

The following day—Sept. 21—there was a sign taped to the side of the campus V. D. C. table, announcing a general membership meeting that evening. It was scheduled for 7:30. but by 8 o’clock the 300-seat campus lecture hall was only half full. I had expected to find a fairly homogeneous collection of beatniks, but it wasn’t quite that simple. Some had long hair and scraggly beards and in many cities would have been arrested for vagrancy on sight. But for every kook there was another young man with short hair, shaved chin and clothes that were presentable if not stylish.

There was also a handsome man whose auburn beard concealed his face as well as his age. He smiled quickly and well, with little wrinkles at the corners of his eyes. This was Steve Weissman, one of the articulate leaders of last year’s campus demonstrations—the Free Speech Movement—and now a driving force in the V. D. C. There was also Jack Weinberg, another popular leader of the F.S.M. Weinberg was wearing heavy pants, a wool plaid shirt and lumberjack boots. He had less humor and style than Weissman, but Weinberg looked like a fellow who had been around. When he spoke, people listened.

[Jentri’s note: People listened because he was the hero of the FSM.]

The man I had buttonholed at the campus table was there, too. He turned out to be Jerry Rubin, a non-student who had traveled to Cuba in 1964 and who was credited with suggesting the “Days of Protest” which were coming up in mid-October. He was a small, irritable fellow, and his favorite expression

Berkeley

CONTINUED

seemed to be, “Well, I don’t want to talk about that now.”

[Jentri’s note: When Jerry Rubin showed up on campus after the FSM and began speaking at the noon rallies now (because of us) a fixture on the Sproul Hall steps, everyone I knew was appalled. He had an anti-intellectual tone, lumped the faculty together as all bad–which insulted me in particular because I had the deepest respect for some general actions of the faculty and for particular anthro professors,– and, in the deepest possible contrast to Mario Savio and most of the FSM leaders, shrieked and dumped on us for NOT BEING ACTIVE ENOUGH. We certainly did not feel that we needed any guidance from the likes of him.

We were especially pissed at him one day when he referred to “what we did in the FSM.” In the break room that day we were all saying to each other, “what you mean WE, a-hole? You weren’t even here.” That he should imply that he was a participant and then be so embarrassingly unlike our FSM leaders was a hard thing for us to accept. I never followed Jerry Rubin anywhere. In the VDC, I was following Weinburg, Bardacke, Weissman and my anthro colleagues.]

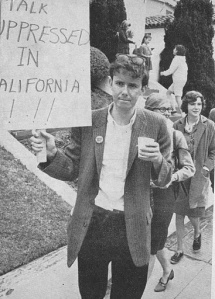

The author joins pickets at California Governor Brown’s house in San Francisco. This venture was a bust; only 20 people showed up, and they learned Brown hadn’t lived in this house for five years.

[Jentri’s note: Later in this article, this author mentions that there was surprisingly little social contact between VDC activists outside the VDC. I found that hilarious, since this picture proves I was doing my damndest to socially interact with him. I had spotted him early on this day, had thought he was awfully cute and seemed to have a very balanced, calm, rational aura about him that I liked. Plus, he spoke knowledgeably about the issues. He clearly knew more than I did about Vietnam. I maneuvered to be in the back seat of the car with him as we drove to this demo, and flirted with him in my probably-too-subtle, dignified way all the way there, then made sure I was right behind him in the line, in case we should take a break and I could renew my efforts. I never suspected for a minute that he was a news-mole.

That’s me, seen partially, with the glasses. My relationship with my more or less boyfriend contained no promises of fidelity and this was at a time when we were, as the phrase went later, “giving each other some space.” I would have had social and other kinds of contact with this guy in a flash, had he been open to it, but, alas, I guess he just wasn’t that into skinny, brainy, bespectacled women.

In other news, it was very rare for me to participate in such a half-assed event, and I think this might have been the most half-assed one I ever did participate in. I was normally much too busy working half-time and maintaining my 3.6 GPA. It just so happens that I had nothing pressing to do that particular day, needed a break from work and didn’t feel like being alone.]

During Oct. 16 march shown on pages 108-109 VDC’s Jerry Rubin holds a sound-truck mic to make people stay in an orderly line.

‘A chance they can call it treason’

A few chairs from me a slightly overweight, unhappy-looking girl pushed her knees into the seat in front of her without regard for her skirt, and I couldn’t help thinking she would look terrible in slacks. (It turned out 1 was right when I saw her again a few days later.) Then the meeting started. The first order of business was a report from a member who claimed he had discovered that the Army was training guard dogs (“killer war dogs,” he called them) in an abandoned Nike missile-launching site near a public park. He said he had scouted the place and hinted that he had a program of harassment worked out.

The meeting moved on to the question of the October demonstrations. From the drift of the talk I gathered that there were two camps. One group—someone called them “the hawks”—wanted to continue with “civil disobedience” at the Oakland Army Terminal; blocking gates and rail traffic, perhaps climbing the terminal fences. The “doves” wanted to substitute a campus teach-in, a peaceful parade through Oakland and another teach-in in a vacant lot opposite the terminal.

“Listen, I’ve been talking to some lawyers,” one speaker said, “and it sure looks like we’ll wind up in a sling if we start blocking traffic around that terminal. That’s federal property, and there’s some chance they can call it treason.”

Treason! There was a great inhaling of breath. People looked around at one another, calculating how long 10 years in federal prison might be. Later, in conversations with various V.D.C. leaders, I got the impression that more than fear of prison was involved; the “peace movement” liked its new respectable image, and civil disobedience would disfigure that. Anyway, the doves won the vote, as they had in the past and as they would again. A V.D.C. vote, I was to learn, is never really conclusive unless it has been taken several times. The pattern of the October demonstrations was now set. Then a collection was taken, and nearly everyone put money into round cardboard canisters. A few stuffed in dollar bills.

“Is everyone here a member?” someone yelled.

“No,” I shouted back.

“Good,” the first speaker said. “You can get your membership card right here, for 25 cents.”

The meeting resumed. A film was shown—a half-hour documentary by a Japanese cameraman who had spent a few days with a South Vietnamese Ranger battalion. We were told the English soundtrack, in a woman’s voice, had been taped in Ann Arbor. Mich. The words didn’t match the pictures. Soldiers and civilians were shown standing up during “battle” scenes in which they supposedly were being machine-gunned. We saw the Rangers kicking a few V.C. suspects around, but most of us had seen more torture at prizefights.

The only scene that drew much comment was supposed to show the Rangers shooting a V.C. suspect in the back. But only a halfdozen frames flashed on the screen, like a filmstrip, and these were hopelessly blurred.

A tall, heavy-set man objected, “That looked phony as hell. What happened to the rest of the scene?”

The girl who had arranged for the film said the Japanese government had censored it. Nevertheless the committee agreed to buy it–for $500. About a week later, when someone asked about the film, the V.D.C. finance chairman, Larry Loughlin, said we hadn’t been able to raise the money. The finance chairman always looked worried, and with reason, since the V.D.C. was always broke. Loughlin would run his fingers through his hair and begin a financial report with a pained look and the news that the printing bill was $500, the rent was due and there was $128.50 in the treasury. I was pleased when someone said he was dating the only truly beautiful girl on the committee; this unhappy fellow deserved something.

[Jentri’s note: The sexism that permeated American culture, including Berkeley political movements, is well illustrated in that last statement. In the midst of all this talk about equality and meaning, a woman activist who happens to be “truly” beautiful by the author’s standards is most valuable as a booby prize for a deserving male activist. Referring to the membership cards above, I don’t remember cards or any talk of membership, though there were certainly mailing lists. It would tend to belie my statement above that nobody was ever really a member of anything. Maybe it would be more accurate to say that nobody ever made a distinction between members and participants and decisions were made by whoever was there.]

Loughlin’s finance committee was the only V.D.C. group that was not wide open to anyone who showed interest. I tried to join and was told the committee was “already formed.” Once, in the confusion preceding a general meeting, I sat down beside Loughlin and told him some of my friends were disturbed about the committee’s finances, and that they suspected the V.D.C. was taking Communist money. He seemed to be genuinely shocked.

“Oh, for Christ’s sake,” he said, “that’s silly. Look, we take in anywhere from $30 to $100 a week from collections around campusand elsewhere. We have a pledge

Berkeley

CONTINUED

list of people who donate every month, and that brings in about $600. About once a month we send out a fund appeal—we use the mailing lists of various groups, like the anti-H.U.A.C. bunch—and we send out maybe 10,000 or 15,000 letters. We get a good return on that. I don’t know where people get this idea we’re all getting big bars of gold from Moscow.”

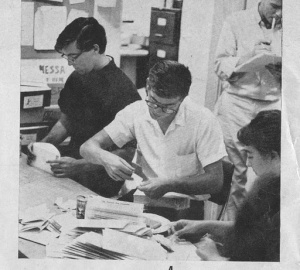

The next day Loughlin and another fellow paid no attention when I began to leaf through their ledgers. The entries tended to con-firm Loughlin’s answer. Most donations were small, in amounts averaging $20. Nearly all were from individuals, although some werefrom peace and church groups. Most donations were signed, although a few came in anonymously, with notes to the effect that “Ican’t afford to get involved personally, but . . .” Two weeks before the scheduled Oct. 15 march the last mass mailing jumped that to nearly $200 a day.

Toward the end of September large signs began to appear on the campus: BIG MARCH ON GOVERNOR BROWN’S HOUSE. SHOW HIM HE CAN’T SUPPRESS FREE SPEECH ABOUT THE WAR. Pat Brown had been an unpopular figure on the Berkeley campus ever since he ordered 600 policemen to haul demonstrators bodily out of the university administration building during last year’s sit-in. This year he had increased his unpopularity among V.D.C. members by dressing down a man named Si Casady, who was president of the California Democratic Council and who had criticized U.S. policy in Vietnam. The C.D.C. is a left-leaning appendage of the state’s faction-ridden Democratic party, and Brown told Casady to keep quiet or get out. (Last week he was still being defiant.)

An organizational meeting was called for 8 o’clock Wednesday night, but it was 9:30 before anyone at the V.D.C. house noticed the meeting hadn’t been held. Everyone had forgotten it. It was held the next night, and those present decided to hold a rallySunday afternoon at San Francisco State College. then march on to Governor Brown’s San Francisco address, nearly two miles away.

On Sunday morning, I drove to San Francisco to scout the scene with Steve Smale, a brilliant, 35-year-old provessor of mathematics at Berkeley and a V.D.C. leader. Smale is a smll man with a thin, strained voice and a forced laugh. He reminded me of Wally Cox’sMr. Peepers.

“We ought to get a hundred people or so out today,” Smale said, mindless of the dreary overcast. “That’s pretty good, isn’t it,for a Sunday morning?”

Smale found Brown’s address—46O Magellan Avenue—then drove over to the San Francisco State campus to collect a crowd. After nearly two hours the best we could do was 20 people, four of them newsmen. We drove back to the governor’s home and got out of our five cars to divide up our picket signs, taking too much time and feeling rather silly. Finally about five people began walking toward the house and the rest of us followed. The picketing had gone on about 15 minutes when a neighbor walked by and said:

“You’ve got the wrong house, kids. Brown hasn’t lived there for five years.”

We all thought this funny, but we kept picketing; we didn’t know what else to do. Anyway, the governor did own the house: indeed, this was still Brown’s official voting address. After an hour we stopped kidding ourselves and went back to the V.D.C. office in Berkeley. As we relaxed there a V.D.C. member said, “What the hell, all marches are symbolic. Take the trains last summer. We didn’t have a prayer of stopping those troop trains. But people saw what we were doing, and they could see that we cared enough to take a chance. It made people think, and that’s why this movement is as big as it is now.”

How big was it? It was such a compact little group, those who were active—300, at the outside. Of course there were thousands of passive sympathizers, and if they wanted to join up we welcomed them as oflice workers (we called those people the “forced labor brigade”) [Jentri’s note: I must have been one of those] or as planners. It remained surprising to me that a man could wander off the street and just join any V.D.C. decision-making body—except, of course,the finance committee.

Committee leaders know this left the V.D.C. wide open to Communist infiltration, real or imagined, but no one cared much. “After all,” said a member in one of the rare discussions I heard about this problem, “if a Communist can bring up a good idea and sell it to the group, that’s one more good idea we’ve got going for us. And if they can’t sell it, then what’s all this nonsense about ‘Communist domination’?”

“Yeah, we’ve probably got some Communists,” another member told me later that evening. “Jay has an active C.P. backgroundand Jim probably does too. And a lot of the guys we’ve got are from Progressive Labor~that‘s a Maoist bunch, you know. And, you know, there are a lot of people here who are Marxists or Trotskyites. But what the hell, that doesn‘t mean they’re taking orders from Moscow or anything.”

“Besides,” another chimed in, “I don’t think it makes much difference. A lot of the people here don’t have that deep a political commitment. I mean. I’m here because I don’t like the war. I mean, nobody likes war, but some people have different reasons for not liking it. Dig?”

That same weekend a meeting of the new Anti-Draft Committee was scheduled at V.D.C. headquarters. I was a member, and a dozen of us waited more than an hour for Steve Cherkoss, the chairman, to arrive. Cherkoss, a former Berkeley student and now an active Progressive Labor man, is built like a stevedore and talks in waterfront idiom. He mumbled an apology for being late,took off his coat, sat down backward on a chair and began a long, rambling discussion of military conscription.

“Well, we gotta do something about this. It’s undemocratic. I mean, they take a guy and make him go off and do something hedoesn‘t want to do. Its a lousy system. You know, there‘s an office here that tells the Selective Service who’s making good grades and how many hours everybody’s taking. So the university’s really kind of a fink outfit. . . “

“Well,” someone interrupted, “what can we do about it? lt’s not enough just to sit around and hate it, you know.”

Cherkoss looked hurt and said:“Well, we can screw it up. I mean like, for instance, we can get guys to claim C.O. [conscientious objector]. A C.O. petition takes about a year to process.”

“Supposing it doesn‘t work,” a young-looking fellow with a wispy beard said. “What happens if they reject your petition?”

“You can appeal it.” Cherkoss said. “Hell, they’ll probably reject everybody’s petition to begin with,but that doesn’t make any differ- ence. If we can get enough people to fill these things out, it‘ll clog up the war machinery. Right?”

“Look,” said The Beard, “I don’t want to clog up anybody‘s machinery. I want to keep my tail out of the Army. You guys can sitaround and talk about ethics, but I’m not in school-—I don’t have a deferment—and I want to know how to beat the draft.”

For the next few minutes we discussed ways to beat the draft.

“O.K., everybody knows a different way to beat it,” someone finally concluded. “Some guys say they got trick knees. Some run upand kiss the doctor. You know, claim they’re queer. Some guys can flunk the mental test. What we ought to do is collect all these things and put’em in a leaflet.”

‘‘I guess that’s O.K. if you want

CONTINUED

to lie,” said a serious—looking fellow named Mark. “But I just don‘t think it’s very ethical. Even with the C.O. thing, you’re playing the system, you’re doing it the government’s way, by their rules.”

“Yeah,” another said, “if you cooperate with an unjust system, you’re really helping it. If you’re really serious about opposing the draft, then you’ve got an ideology to answer to, don’t you see?”

‘‘I’m not sure we’ve all got the same ideology,” another said.

“Guys who want to go C.O. can take that route, and guys who don’t mind playing fag can do that, or take dope or flunk the mental test. And if you want to refuse to cooperate, then, hell, that’s your bag. But not everybody’s ready to go that far.”

As was always the case at a V.D.C. meeting, no real consensus could be reached.

The week following the Brown March (or nonmarch), the V.D.C. savored a Moment of High Glory. It had to do with those Army “kill-er dogs.” Since the first general membership meeting I attended, a small team of V.D.C. “Peace Commandos” had spent their afternoons trying to make life miserable for the soldiers who were operating the guard-dog training camp. They plastered nearby Tilden Park with signs: “CAUTION: Army War Dogs in This Area . . . Keep Children and Pets Within Sight. lf Dog Approaches Do Not Move. . . .”

The Army was quick to point out that the dogs were always kept fenced and under supervision; but then, one Monday afternoon, a tall, tense young man named John Seltz came bursting in with the news that he had found a gaping hole in the fence.

“Those dogs can roam all over the countryside,” he said, “eating up little children and tearing out people’s throats.”

He smiled a thin, put-on smile and said he planned to take a task force up to photograph the hole. I volunteered to take the picture. The next morning five of us gathered—Seltz, a sad-looking girl who seemed to adore him, two other men and myself. We piled into Seltz’s van and began the winding, uphill drive.

Seltz was the V.D.C.’s top commando, an activity he preferred to theoretical discussions. He was not a student, although he said he had come from Illinois a few months earlier to study architecture, hauling all his belongings—including his motorcycle—in the back of this van. We parked at a scenic lookout and started walking. The Nike site was located just north of the Tilden Park lookout point and, ironically, near a Rotary-sponsored Peace Grove. It was a three-mile hike. The girl walked ahead and,by the time we climbed to the top of a little peak, puffing and panting, she was pointing excitedly toward the Nike site.

“They’re gone.” she yelled, “the kennels and the dogs and most of the men—they’re gone!”

Indeed they were. Below us, a quarter mile away, soldiers were packing things into trucks. We danced around excitedly and I took some pictures of our group, including a “planting the flag” scene, using the peace flag we had brought. The Army said it had been planning to move out anyhow. The V.D.C. claimed a clear-cut victory for the Forces of Peace and Good.A few wanted to throw a party to celebrate, but since a fund-raising party was scheduled for the following weekend, we decided to wait.

The fund-raising took place in a Berkeley home—a pleasant, modern house with dark wood paneling which someone called “middle-class professorial.” The door was open all evening and, whenever someone walked in, a determined-looking girl would thrust a cardboard container forward and demand a dollar donation. People bought whisky or beer for 50 cents, and stood around and talked about Vietnamese politics and the anti-war movement. They were pleasant but not particularly friendly; a stranger knew that he was a stranger.

I drifted from one conversation to the next, listening in:

“So this heckler is giving me a real bad time and I say. ‘If you like this war so much. why aren’t you fighting in it?’ and he sayshe’ll go fight when they call him, and I say, ‘Well, I’m fighting for peace right now, and I didn’t have to be called,’ and he got mad and left.”

“Look, if the cops bust us for anything, we’re going to be in trouble. We just don’t have the dough for bail.”

CONTINUED

‘If the cops bust us, we don’t have dough for bail’

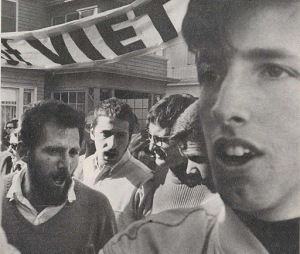

Mike Myerson, a former student, visited North Vietnam in September (top picture). A month later, now shaven, he was in the Oakland march (bottom picture).

“I hear they’re drafting students at Michigan now.”

“My brother-in-law knows a guy who’s in the National Guard and he says, if we try anything around the Oakland Terminal, they’re really gonna bust some heads.”

“I don’t think we’ll get that far. I think Oakland cops’ll nail us first.”

“Hell, we could start pulling troops out of there tomorrow, but Johnson and Bundy and the rest of those phonies are afraid to do it. They’re afraid to admit they’ve been wrong all this time.”

“People won’t start screaming about it until their friends start coming home dead. I bet if people knew how many guys were reallygetting shot there’d be a lot more to our movement.”

“Most posters are fine, but I’m going to suggest we not do the ones that say. ‘The Vietcong are our brothers.’ l’m not sure everybody feels that strongly. And besides, it’s bad publicity.”

After a while a girl in tight pants and a black sweater began to dance the frug as the rest of us watched. For people who were together day after day, we had surprisingly little social interest in each other. I asked a girl about this. It was getting late, and she swayed slightly as she said. “If you ask me, they’re all too goddam busy trying to save the world.”

[Jentri’s note: Regarding the girl allegedly dancing the “frug”, I had never heard of the frug and no one in my crowd danced any dance that was named, except in satire. Furthermore, though I would not dispute such an airhead might have been in and around the VDC office, I certainly never heard that opinion expressed there or anywhere else and if I had, that woman could assume she would never be a friend of mine.]

‘There’s thousands of people ready to march, right now’

On Thursday, Oct. 14, the day before the big teach-in and march—it began to rain. About 15 people sat around that afternoon in the V.D.C. office in a massive funk.

“What if it keeps on raining?”

“Maybe it’ll stop. God is on our side, isn’t He?”

“Very funny.”

But Friday morning the sun rose bright and a good breeze blew the clouds inland. By 10 a.m. the breeze had blown itself out and the large campus field adjoining the Student Union building was comfortably warm, ideal for an outing. The teach-in began about noon, with folksingers drawing the first crowds—2,000 or 3,000 people. Behind the stage we made plans to pass the hat every hour or so (the first pass brought in about $500), and crowd-control monitors tested their walkie-talkies.

The list of speakers represented a lot of compromises. There were good speakers available whose airfare we couldn’t afford, and unin-spiring speakers who would come for free. Some were serious, like M. S. Arnoni. editor of a pacifist magazine called Minority of One, who appeared in his Nazi-made prisoner-of-war uniform, and Paul Goodman, a writer and a respected critic of U.S. education. Paul Krassner, editor of a freeswinging pulp magazine called The Realist, spoke two or three times and stuck hard by the speakers’ platform to fill in gaps. During one lull he made some of the purists wince:

“. . . They say nothing about photostats. So those of you who have access to photostatic machines, you can just make photostats of your draft cards and destroy them in public if you like.”

Most of the crowd was delighted, but a purist sitting next to me grumbled, “Burning a photostat of your draft card is like kickingover a toy locomotive and then saying you derailed a whole troop train. lt’s insincere.”

At 6 p.m. people began to drift away for dinner, and most of us worried if anybody would come back for the march. All along we had predicted 5,000 people would march. Now we wondered if we would see 2,000. When I came back at 7 p.m. I was flabbergasted. The last bits of sunset were falling into the bay, and in the black-orange light thousands of people were milling about. Some were curiosity seekers, of course, but to this day I don’t know where they all came from and I don’t think anyone else in the V.D.C. knows either.Steve Weissman was writing out a short speech in the erratic glow of a flashlight when Jack Weinberg came running up, excited and panting.

“There’s thousands of people out there,” he said. “They’re ready to march, right now. Let’s get out there. It looks bad.”

Weinberg dashed back into the crowd, and like a quarterback behind a guard I followed. The people were not just standing on the campus; they were spilling onto the sidewalks and into the street. Hundreds were pushing out to stall traffic. Weinberg grabbed a bullhorn and began to talk in a high, excited voice.

“This has got to be a peaceful march,” he said, squinting into the TV lights. “We’ve got to keep it under control. We can’t get bustedon this march. You can’t run a movement from inside a jail. I know, I’ve been busted before.”

It did little good. People spilled around Weinberg and began to head down Telegraph Avenue. Two monitors carrying a banner dashed to the front of the wall of people, and the sound truck that was to have led the march roared down a side street for two blocks, then cut around in front of the parade. V.D.C. leaders plowed

CONTINUED

‘We don’t have any control, they aren’t ours any more’

through the mob, finally reaching the head. It was a mess. Instead of filling the right-hand lane of traffic, as planned, people spilled across all four lanes of Telegraph Avenue and onto the sidewalks. Shopkeepers locked their doors. We began to sing freedom songs, but with thousands of people pushing us on it was hard to keep rhythm.

The V.D.C. leaders tried to walk at the head of the parade, just in front of the banner, but enthusiastic marchers kept brushing past them.

“Please,”the sound truck kept blaring, “if you’re with this march, if you support us, please keep behind the banner. Keep inline.”

No one paid any attention. After eight blocks a monitor rushed up with the news that the tail of the parade hadn’t left the campus yet.

“lt’s tremendous,” he yelled, “Tre-mendous!”

But the V.D.C. leaders looked scared. “Advance scouts” radioed that a few blocks ahead a wall of helmeted policemen stood on the Oakland-Berkeley line with clubs and gas masks. In front of them, between the police and the marchers, stood a thousand hostile demonstrators.

Weinberg and Frank Bardacke, two members of a hastily formed emergency executive committee, ran forward to negotiate with the

police. They came back to report that the Oakland police were refusing to do anything. Bardacke later quoted Oakland chief Edward Toothman as saying. “You should have thought about things like this when you young people started this thing. I warned you.”

Now the parade stopped, 100 yards from the Oakland city line. The leaders decided to try a flanking movement. Using the soundtruck and bullhorns, monitors and leaders told the crowd the parade would turn right, travel on a few blocks, then turn left to parallel the original route of march.

But as we swung into Prince Street, narrow and residential, the leaders became more and more nervous. The crowd was anxious to swing left and confront the Oakland police. The marchers began to chant:

“Left! Left! Left! Left!”

“We can’t turn left,” Weissman told the other leaders. “We don’t have any monitors, we don’t have any control, we don’t have anything!”

The leaders had been prepared to lead 5.000 people, but they were clearly over their heads with l4,000.

“They’re not ours any more,”someone said, shaking his head. “They‘re not anybody’s.”

We marched a few blocks farther and reached a main intersection. To the left was Oakland; to the right, Berkeley. A scouting party

radioed, “lt‘s clear all the way into Oakland.”

Here the committee had to decide. Should it take the crowd left and risk a confrontation with the police and with hostile demonstrators? Or should it play safe and return to Berkeley? The leaders remembered Weinberg’s warning: “We can’t get busted.” They swung the banner to the right and, despite some mild grumbling, the crowd followed back to Berkeley.

Six blocks behind the banner, a short, squat marcher trudged along in blue jeans, a sweatshirt and a heavy coat. He had a sleeping bag on his back.

“What’s goin’ on?” he asked a radio-equipped monitor. “It looks like we’re goin’ back to Berkeley.”

“Yeah.” the monitor said. “We couldn’t get through the Oakland cops.”

“Hell,” muttered the marcher, “I’ll bet we didn’t even try.”

‘The police have formed a new Berlin wall’

The long walk back to Berkeley was, as they would say. a drag. We trudged into Berkeley’s Civic Center Plaza, where the leaders had announced we would hold the all-night vigil. Next day, they said, we might try to march again. About 5000 of us milled around in the dark. Some hostile types joined us and there was a brief scuffle. A teargas canister came whistling over the top of a building, but in a minute or two the wind blew the gas away. By 2 a.m., only 200 people were left. By dawn there were fewer than 100.

By ll a.m. the teach-in had begun again. First one speaker, then another took the platform to criticize the V.D.C.’s leadership for “backing down” the night before:

“All we did is go for a long walk. We didn’t even see the cops.”

Off in a clump of bushes, the Emergency Committee met. We would march again, in the daylight. It was a bold but sensible

CONTINUED

idea, and the crowd loved it. The march began at 2 p.m. and was a model of order. Monitors were in control. Everyone stayed behind the sound truck. The leaders joked and laughed and sang, and we all felt as if we were making up for the previous night’s fiasco. Then, as the soundtruck approached the Oakland city line, we had chilling news. Everyone stopped singing: two dozen Hells Angel—members of an unruly motorcycle club that loves trouble—were standing at the city line.

The soundtruck stopped 10 yards from the Oakland policeline. Accounts of what happened next conflict, but in any case, a half dozen Angels came storming into our ranks to grab a V.D.C. banner. Fists swung, people fell and three or four Berkeley policemen waded into the fray. One of them was knocked down. Then that whole wall of Oakland policemen—hundreds of them—came rushing forward, all boots and helmets and clubs. I had been taking pictures and was poised to shoot another when instinct told me to run for it. I wheeled around, tripped over a girl and sprawled to the street. I curled up and waited to be trampled.

But the charge had stopped. In seconds it was over. On orders from the monitors, the crowd began to sit down. A Berkeley police sergeant was carried out, his leg dangling. We all cheered him. Then an Angel was led away, his head matted with blood. We let him have the West Coast equivalent of a Bronx cheer.

The Oakland police reformed and backed up about 50 feet to where they had been originally. A thin line of Alameda County deputy sheriffs stood between us as a buffer. We sat there in the sun for an hour while teach-in speakers talked about the war—and now about a new issue.

[What is important to me about the Hell’s Angels incident is that it inspired my first and only public speech outside the anthro department during the 60s. I had been about three people lines back from the front of the march, close enough to see the charge of the bikers and to have had to scramble to stay on my feet when the people in front of me backed up precipitously. It had been terrifying to me and I was deeply grateful that the charge had been stopped by the police. At a meeting held on campus soon after this march, my anthro friend who was close to the leadership of the VDC was leading a meeting–maybe a work group, maybe a general meeting. It was in a hallway somewhere, people were crowded close together. He was asking for input on what to do next, but people were strangely devoid of ideas, possibly still in some kind of shock.

So I thought “what the hell” and stood up to say what I had to say, which was, “I am very concerned about the officer whose leg was broken and I’m very grateful to him for trying to protect me. The first thing I would like to see is the VDC sending him some flowers and a nice note, could we pass the hat for that?”

This offering was met with a bemused silence that then turned to some angry outcries that he was doing his job and he don’t need no flowers, essentially. My friend who was leading the meeting favored me with a look of supreme scorn and I knew this tale would be passed around the department with raucous derision, so I sat down and shut up.

My friend ignored my suggestion completely and called on other people, now raising their hands with enthusiasm. I guess I must have cracked something open in their heads, undammed the idea block, something. At the time, I was embarrassed, but now I’m rather proud of myself and feel the story speaks to my integrity rather than my naivete, even though my naivete famously led me into being the scapegoat for department activists later, during the People’s Park controversy.]

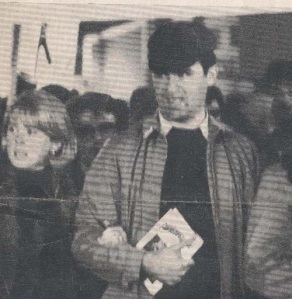

Five minutes before violence broke out, V.D.C. leaders Steve Weissman (beard), Jack Weinberg (center) and Frank Bardacke (glasses) had strategy talk. [Jentri’s note: the guy in the foreground is not identified.]

“The Oakland police,” said one. “have formed here today a new kind of Berlin Wall, a Berlin Wall of America. They have said we cannot march to protest the war. We must break down that wall. We must march again and again and again if necessary, to show them there can be no such wall in America. We shall win!”

We sang a final chorus of “We Shall Overcome.” and headed for home.

It suddenly seemed lonely out there in the setting sun. I saw a girl I knew and we walked back together. After about a mile we caught a ride with a friendly mother who had brought her children down to watch the fun. She gushed a bit over what a good thing the march had been and said that next time she was going with us.

That night we had a rather quiet party at Steve Smale’s house. Everybody stood around and drank and got a little tight, but things began to drag about 1 a.m. For the first time in weeks, no one wanted to talk about the march.

Sunday the V.D.C. house was almost empty. The floor was littered with papers and old posters, and empty beer cans were stacked in wastebaskets. The office was clearly dark; no one had bothered to replace burned-out light bulbs, and only two or three worked in the whole house.

“Guess we held the march just in time,” someone said. “Another week and we’d have been in total darkness.”

By Monday, Oct. 18, my last day with the movement, some of the old snap had come back. Someone had finally installed a couple of new light globes, and a half dozen people were typing, answering the phones and looking busy.

“What’s everybody doing here?” I asked, half in jest. “Don’t you know? We‘ve already marched. It‘s all over.”

A girl who was typing snapped around and looked surprised.

“The hell it is,” she said.

[Jentri’s note: I’ve always wondered if I was this “girl”. I don’t remember doing this, but I could well have been there that day typing and it is certainly something I might have done and said. On the other hand, it was 50-plus years ago and I’ve read this article so many times, its hard to separate it from my own memories.]

I am often contacted by persons wishing to interview me for oral histories of the 1960s because of my participation in the documentary film, “Berkeley in the Sixties.”

I am often contacted by persons wishing to interview me for oral histories of the 1960s because of my participation in the documentary film, “Berkeley in the Sixties.”

Jentri: a very interesting commentary. I was involved (but as a Trotskyite infiltrator) in the VDC in

1965-66. It’s really very difficult, if not impossible, to explain to young people today, what those times were like, and how people could believe and do things which now seem so foolish. But you seem to have made good choices in your life. Thank you for creating this bit of historical documentation.

Spot on with this write-up, I truly think this website needs

a lot more attention. I’ll probably be back again to read more, thanks for

the information!

[…] 1997. Berkeley In the Sixties, directed by Mark Kitchell, 1990 (available on-demand on Netflix). “Vietnam Day Committee,” Jentri Anders’ Berkeley Backlog, November 2011. “Interview with Frank […]

Nice piece. Good physical descrip of John (Seltz). I remember the VDC night march and the turning onto Prince St.–I’d climbed up on a car to watch the “leaders” and cops conferring in the stand-off–very tense moments–but I left before the turn right toward Berkeley.

My recollection of the Sunday afternoon march was that the Berkeley cops, rather than sheriff’s deputies, were who stood between the seated demonstrators and the Oakland cops. But, as Gentri says, this was all a long, long time ago. And so I’m not really sure.

I actually use the evening march (and the ’65 second trooptrains demo) in my forthcoming Reaching Through/ 65-69 novel of the Movement (and have a character based partly on Seltz), so it’s interesting, and sometimes amusing, to read others’ takes on . . . well, on what became soon so much of who we still are.

Hey, so sorry I can’t keep up with blog comments and am replying months after the fact. I would not swear to the certain identity of any of the cops who were part of my life in Berkeley, except the campus cops. I know I remember them right. I was in so many demos and so many different kinds of cops were at each, you may very well be right. I will be interested to read your novel when it comes out. I can only do memoirs at this point, graduate school having ruined all my creative skills, though I will advise my readers in the preface that I can’t always tell the difference, in minor ways, between what actually happened and how I have come to tell the story over the years. I will tell them, if you don’t believe me, just pretend you’re reading fiction, its still entertaining and useful.

Hi Gentri, Listen, I shall be reading from my new novel–the on the Berkeley antiwar movement–on May 25, 12:15pm, in the auditorium of Berkeley City College, 2050 Center St. It would be great to actually meet you–if you get this post on time–if you would like. I’m not sure which part I’ll be reading from yet–maybe the part about meeting Seltz, when he brought in a story when I worked at the Barb–or maybe a piece from the Port Chicago demonstrations part. In any case, I suspect there’ll be some other movement vets there. –Oh, please feel free to let people know of this! My best to you, and when I get back from my trip to Berkeley for this, I’ll respond in more detail to your own comments here. They are so evocative Best to you, Paula

The “complainer” woman must have been the wife of William Mandel, who had a 15 minute commentary spot on KPFA in the 1980s. We lived down the street from him, and she was probably the woman who was quite rude to my kids on Halloween, giving no candy and telling them to go way because she had guests coming.

Ok, very long response time. I’m very unteach and just found your ancient comment. But, what the hell, maybe you’ll see it someday. Yes. That’s exactly who it was. One of the witnesses told me that later.